Understanding how animals use space is a central question in movement ecology, and home range estimation is a key tool for answering it. Home ranges represent the areas an animal regularly uses to meet its biological needs, such as foraging, resting, and mating. Over time, ecologists have developed a variety of methods to estimate home ranges from location data, each with strengths and limitations, including Minimum Convex Polygons (MCPs), Kernel Density Estimates (KDEs), and Brownian Bridge Movement Models (BBMMs). MCPs connect the outermost recorded locations to create the smallest convex shape that contains all location points, but this often overestimates space use by including unused areas. KDEs improve on this by estimating the intensity of space use (“utilization distribution”) based on point densities; however, they treat locations independently and ignore the sequential and continuous nature of animal movement. I used KDEs for my own master’s thesis on the movement and territoriality of owl monkeys in the forests of Argentina, for example.

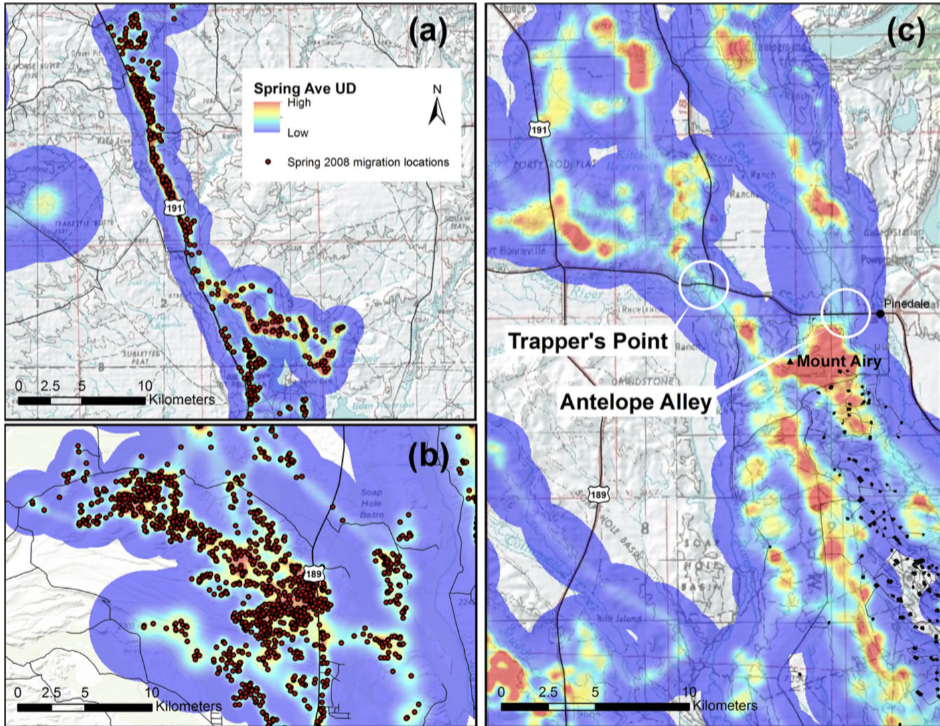

BBMMs address many of the limitations of the other home range estimation methods by

incorporating both the time elapsed between GPS fixes and the probable paths traveled between them (although they assume animals move randomly instead of directedly), calculating the intensity of space use similarly to KDEs. This makes BBMMs especially powerful for interpreting movement data in a more biologically realistic way, particularly for the mapping of migratory corridors, stopover areas, and habitat preferences for example.

Pronghorn (Antilocapra americana) are one such migratory species to which BBMMs can be

useful for understanding their movement patterns in their search for food, water, and mates that other methods might miss. The insights gleaned from pronghorn BBMMs can inform conservation efforts, from helping identify pinch points where habitat connectivity is most at risk, to guiding mitigation efforts like fence modifications or wildlife crossings. BBMMs are most often applied to migratory birds and sometimes to migrating ungulates, but have only been applied to pronghorn a handful of times such as in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (Seidler et al. 2015) and in Wyoming (Xu et al. 2023). As a side project, I am working on building BBMMs for pronghorn movement data in southwestern Montana generously shared with me by our western partner, the National Wildlife Federation.

References

Seidler RG, Long RA, Berger J, Bergen S, Beckmann JP. 2015. Identifying impediments to long-distance mammal migrations. Conservation Biology. 29(1):99–109. doi:10.1111/cobi.12376.

Xu W, Gigliotti LC, Royauté R, Sawyer H, Middleton AD. 2023. Fencing amplifies individual differences in movement with implications on survival for two migratory ungulates. Journal of Animal Ecology. 92(3):677–689. doi:10.1111/1365-2656.13879.

STUDENT RESEARCHER

Jeremy Pustilnik, Research Assistant | Jeremy Pustilnik is a Master of Environmental Science candidate at the Yale School of the Environment (YSE) where he works on the movement ecology and territorial dynamics of Argentinian owl monkeys. He received his B.S. in ecology and evolutionary biology from Cornell University where he worked on the predator-prey interactions between foxes and rabbits at groundhog burrows, the movement of stone martens across the Mediterranean, and the population ecology of salamanders. Prior to YSE, Jeremy worked on the tundra of the Arctic Circle with the USGS monitoring goose and shorebird nesting success and in the desert scrub of central Texas on the disease ecology of mice and metacommunity dynamics of soil arthropods. With Ucross and the National Wildlife Federation he is working in GIS to develop landscape models of pronghorn movement and the implications of wildlife fencing in the American West. In his free time, he enjoys flipping over rocks and logs to find snakes and bugs, flying his drone for service projects like mapping local parks, and reviewing scientific manuscripts for the journal Urban Naturalist, at which he is an editor. Blog