Over three years have passed since voters approved Measure W in 2018 to increase water supply, improve water quality, and provide overall community benefits to Los Angeles County. Now approaching its third funding cycle, the Safe Clean Water Program (SCWP) is confronting more questions than ever about how to invest in the region’s water future.

Even without a formal declaration of statewide drought, efforts to combat water stress are already underway in Southern California. Huge investments are being made to move the regions’ water supply portfolio away from imported water from Northern California and the Colorado River and toward locally-controlled resources through conservation, wastewater recycling, groundwater cleanup, and the subject of LA’s SCWP: stormwater capture.

Dry weather runoff on its way to the LA River. Photo by author

Large-scale stormwater capture projects, such as centralized spreading grounds, and smaller ones like cisterns, bioswales, and permeable pavers, can help slow, filter and capture stormwater and dry weather runoff. In addition to increasing water supplies, stormwater projects can make urban communities cooler, create new open space, reduce pollution in vulnerable neighborhoods, and boost investment where it’s needed most. That is the mission of the SCWP, which strives to implement projects that meet the needs of the local and regional community by delivering multiple benefits.

This summer I am working with the Council for Watershed Health (CWH) to advance the SCWP, identifying opportunities to connect community needs with funding for green infrastructure (GI). CWH, which has been working on distributed GI for years, has recently been appointed to the role of Watershed Coordinator for the Upper Los Angeles River sub watershed. Among other tasks, CWH will be responsible for building meaningful community engagement with the program and charting a pathway that supports grassroots water initiatives.

Bioswales help capture, filter and sink rainwater. Image credit: Council for Watershed Health

While the selection criteria for stormwater capture projects has historically compared elements of cost-effectiveness, water volumes and quality, and service reliability, the Safe Clean Water Program has demonstrated that community benefits of a green infrastructure project deserve greater attention. In order to identify the community benefits of new water assets, we need to understand the varying inequities, challenges and strengths that make up a community. An intersectional perspective at the neighborhood level considers the person’s multiple identities within the context of their environment. It can examine the connection between race, gender, social economic status, housing and food insecurity, health, economic and educational disparities, burdens of climate change, and access to nature and green space. CWH has found that successful GI projects not only address challenges but build off community strengths— whether it be plentiful community gardens, accomplishments in water conservation, local entrepreneurship, or even greater food.

Increasing intersectionality within the Safe Clean Water Program has required unprecedented coordination. The operating mechanisms of the program are complex, responsible for allocating nearly $300 million dollars annually across 87 municipalities and nine sub watershed regions. These sub watersheds are overseen by Watershed Area Steering Committees (WASCs) who are entrusted to award projects based on a high level of accountability towards communities. This structure is helpful in ensuring that local money raised will stay local, while providing an annual (replenishable) fund that is often hard to find for similar capital investments.

Recently, each of the nine WASCs has received approval for Stormwater Investment Plans, which award projects that have scored high across areas of water quality, water supply, nature-based solutions and community investments. Many who have tuned into WASC discussions, which are made open to the public, may have witnessed an underlying tension among Committee Members surrounding the types of projects that should receive funding.

Questions have arisen surrounding the optimal distribution of projects with varying price tags, whether funds should be spent all at once or trickled out, how to include the applicants’ level of need or a projects’ level of support in assessments, and so on. And while a central focus of the program is to fund projects that provide “community benefits,” defining those benefits, as well as evaluating the level of community engagement already completed, has proven to be difficult.

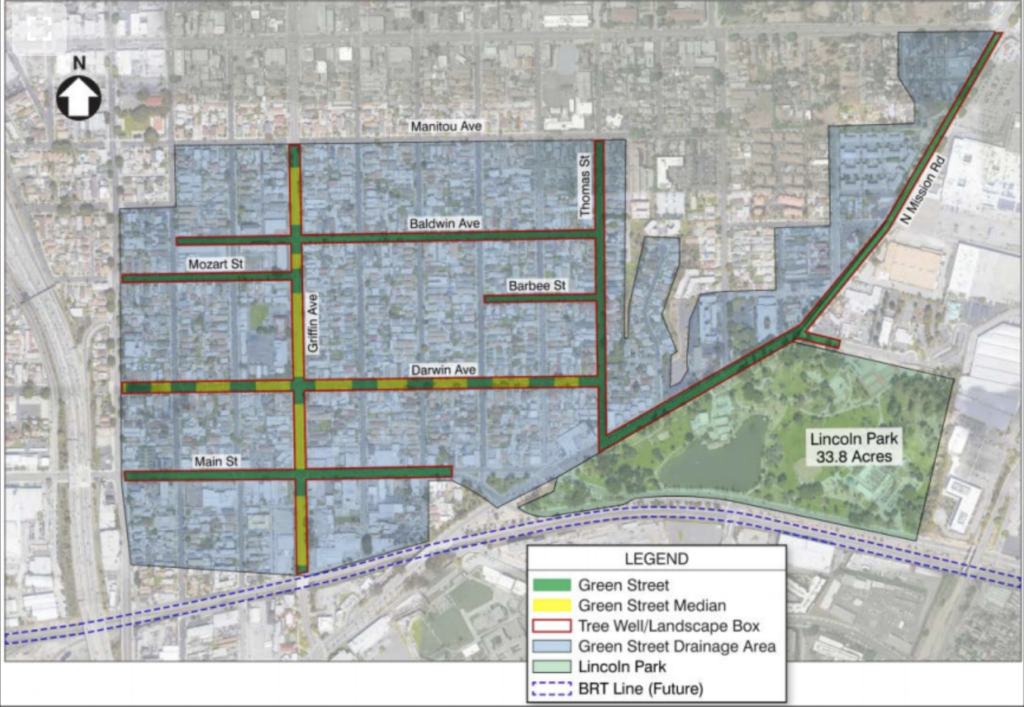

Recently approved for Measure W funding, the Lincoln Park Lake project will capture stormwater through green streets and landscaping to the west of the park. Source: LA Sanitation

As WASCs wrestle to find policies that allow for comparisons of highly varied stormwater projects, efforts are being made to help emerging applicants propose projects with clearly-articulated community benefits. To help bridge this gap and achieve greater intersectionality, Watershed Coordinators, including CWH, have been appointed to each of the nine sub watersheds to develop community input for future rounds of infrastructure funding and solutions. The Watershed Coordinators are responsible for building inclusion and meaningful engagement in the program, connecting potential applicants with technical resources, and promoting collaboration across WASCs.

CWH, for example, is working with community-based-organizations (CBOs), school districts, and small municipalities that are less familiar with GI projects to leverage water dollars that can advance their work while providing previously unplanned water benefits. We have seen that projects backed by diverse coalitions address complexity and lead to a healthy return on investments. For example, Measure W projects can engage young people (e.g., Conservation Corps), previously incarcerated people, and people participating in re-entry programs (e.g., Chrysalis) to not only provide jobs but empower a sense of community.

Moreover, aligning the objectives of multiple institution types will produce benefits beyond water, and secure additional funding streams. In addition to Measure W, multi-benefit projects could garner funding from other local measures (see: WHAM), a federal infrastructure bill and congressional earmarks, and state climate resilience funding. As Watershed Coordinators help bring community voices to the Safe Clean Water Program in upcoming funding cycles, the case for intersectionality will undoubtedly grow stronger. We are facing a monumental opportunity to implement green infrastructure on a massive scale. Let’s make sure we do so with projects that increase the quality of life of our communities across many fronts.

Beyond water quality and quantity, rain gardens offer multiple community benefits: flood mitigation, recreational space, and cooler temperatures to name a few. Source: Council for Watershed Health.

Ryanna Fossum, Western Resource Fellow |Ryanna Fossum is a Master of Environmental Management candidate at the Yale School of the Environment. She is interested in exploring integrated regional watershed management in the urbanized West. Prior to Yale, Ryanna researched California water policy to better engage local elected officials with community-led water resilience efforts. More recently, she worked on a range of urban design projects to confront public space challenges in New York City. She holds a BA from Oberlin College and majored in Geology and Environmental Studies. See what Ryanna has been up to. | Blog