Over my summer as a Western Resource Fellow with the National Forest Foundation (NFF), I spent my time diving into some of the complexities of implementing stream restoration in the West. Whether that was creating outreach materials to communicate the relevance of stream restoration to water rights holders or developing a tool for the NFF to measure the watershed benefits of ecosystem restoration, a river ran through the work. Fittingly, a river also marked its end.

Immediately after wrapping up my work with the NFF, I drove to the desert to spend nine days rafting down the Green River. In northeastern Utah, the Green has formed Desolation and Gray Canyons, a sinuous slash cut deep into the rugged badlands of the Tavaputs Plateau. This slash is a swirling band of green willows and cottonwoods beneath a skyscraping labyrinth of red walls and fractal gulches. Once our group of seventeen entered the canyon at Sand Wash, we also entered one of the largest roadless areas in the Lower 48, where the only way out would be to float 84 miles downriver.

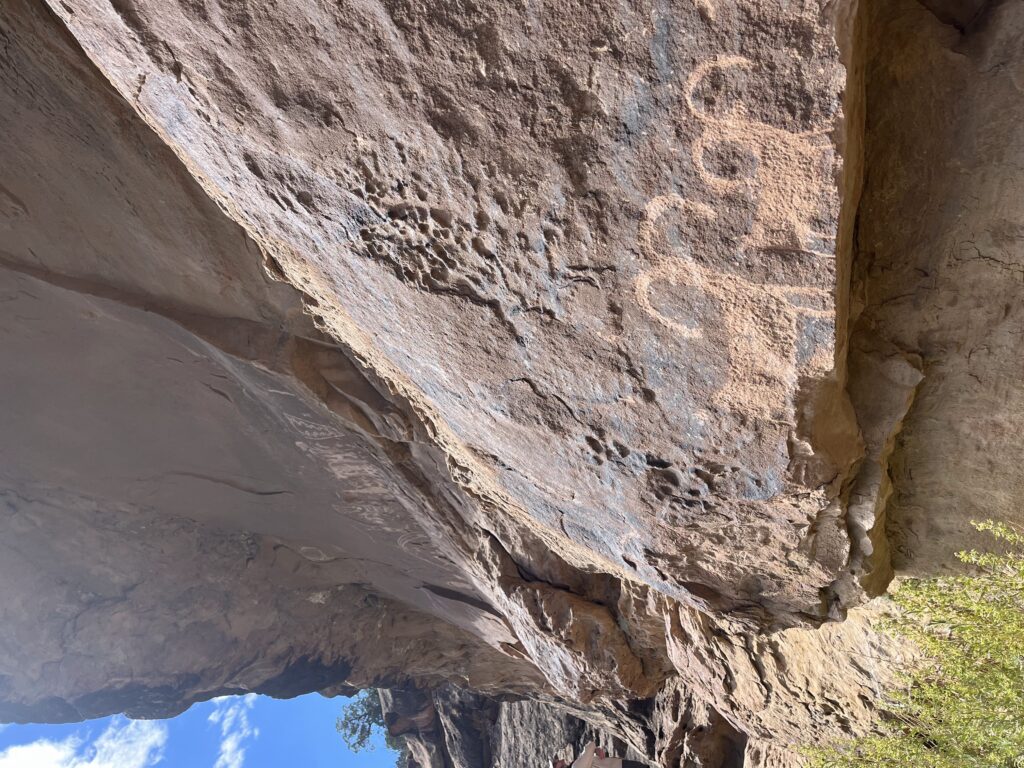

Though it has been over 150 years since Desolation Canyon was so-named by John Wesley Powell—the famed explorer and scientist who led the first American expedition down the Green and Colorado Rivers—it still feels utterly disconnected and wild. Since that 1869 odyssey, the Intermountain West has been degraded, dammed, dried, and deluged with development. Yet Desolation remains desolate. A place where the all-consuming concerns about climate change, politics, and a forthcoming year of graduate school could be left upriver. In their place, I filled up with new experiences: staring into 2,000 year old petroglyphs, playing music around a campfire, scrambling up to old arches, building goofy new friendships, and reforging old ones too, all connected by the river running through them.

When I explain why my mission is to manage western lands to help communities and ecosystems to adapt to climate change, I talk about necessities. About the existential need for communities to receive drinking water, for ecosystems to function, and for livelihoods to prosper. I couch my motivations in protecting the provisioning, regulating, and supporting ecosystem services that seem essential to the survival of the communities and land that I call home.

But after almost one hundred miles of desolate, intricate desert canyon, I am reminded that this is not my full story. If it weren’t for the experiences I have had on these same lands—joyous or challenging or transcendent—not only would I never have started down this path in the first place, but I would have given up long ago. The public lands of the Intermountain West have saved me when I’ve been at my lowest and sustained me when I’ve felt my best. They are what makes my passion for conserving, stewarding, and adapting land a renewable resource, so that I can give back to the places I love.