Is it possible to tell a complete story? I mean, not a good story or a fun story or a scary story; a complete story? One that tells all the parts, doesn’t leave anything out? The type of story you finish and not only think “Wow, I have a holistic and entire understanding of blank,” but actually do have a holistic and entire understanding of blank?

These are the questions I’ve spent my summer stumbling over. When a global pandemic upended prior plans, I thought of how I might meaningfully contribute in a world of social distancing and remote work. I decided to report on my exploration of America’s National Parks; an exploration not through a road trip or old photos, but through data.

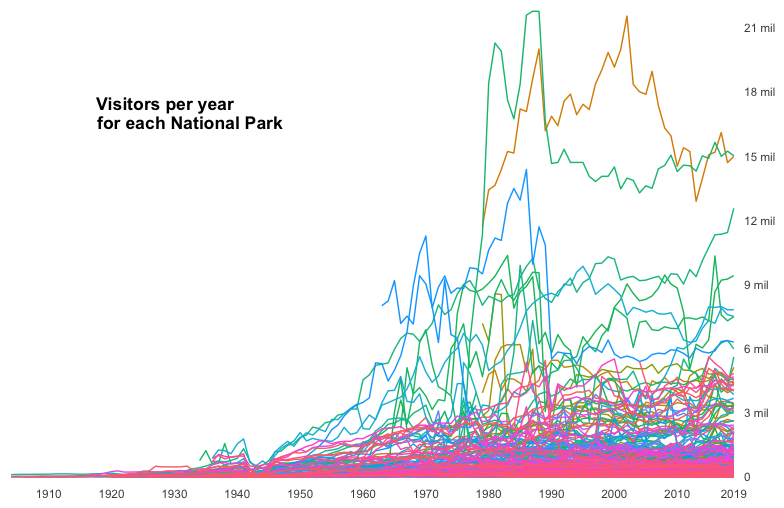

The National Park Service has maintained visitation records for each park since 1904. What I imagine was once a small mountain of meticulously indexed files is now stored in an online database, which anyone can access here. In it you’ll find usage data for national parks, lakeshores, historical sites, battlefields, monuments, and more: 382 different sites. Looking at just the historic annual usage for each of these properties yields 22,457 unique observations. We can summarize them like so:

Figure by author. Data from NPS Stats.

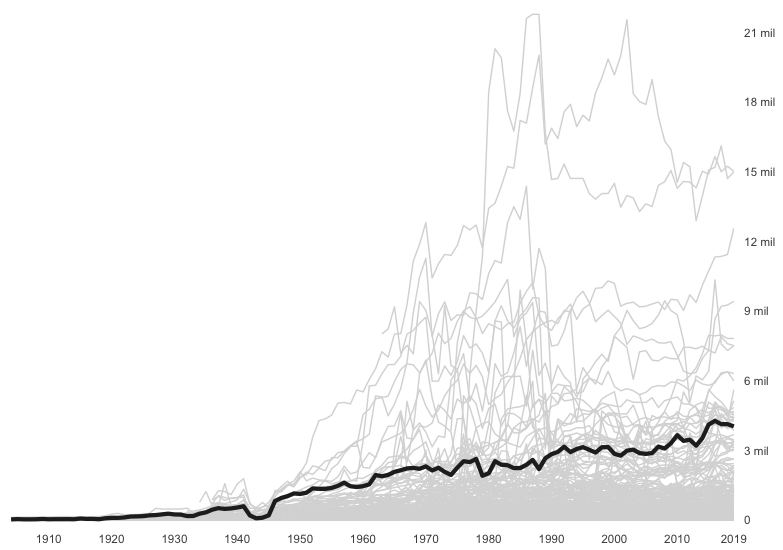

Ugh. What a completely useless figure. This wealth of information, displayed in its entirety, conveys absolutely no information. Put a better way: it conveys no knowledge. Our view is too high up; the details are lost to the scope. The story I set out to tell, the history of the National Parks through data, is nothing more than some squiggly lines of random colors. Perhaps if we zoom in a bit? Let’s take Yellowstone National Park for example:

Figure by author. Data from NPS Stats

A bit better! It conveys a sense of increasing usage of Yellowstone National Park, which is nice to see. It also tells us that recent usage was around four million, usage numbers are higher than the average park, and that a significant drop in visitation occurred during World War II. Fascinating to think that, since becoming a national park, more than 125 million people have visited Yellowstone.

And yet. I’m willing to bet that when you think of Yellowstone, you don’t think of a line drawn by data depicting its historical usage. Maybe, then, the story of Yellowstone is better captured with prose. Perhaps like this:

“The wildest geysers in the world, in bright, triumphant bands, are dancing and singing in it amid thousands of boiling springs, beautiful and awful, their basins arrayed in gorgeous colors like gigantic flowers; and hot paint-pots, mud springs, mud volcanoes, mush and broth caldrons whose contents are of every color and consistency, plashing, heaving, roaring, in bewildering abundance.” —John Muir

For those who have visited, this is a story of Yellowstone that resonates. The land that Yellowstone National Park rests upon is inspirational. The gushing geysers, flowing grasslands, and sparkling canyons induce awe and reverence, well captured by John Muir in his description of the park.

And yet. The National Parks are much more than the land they rest upon. They are also the result of infinite interactions of people: people and the land, land and the people, people and peoples. Muir, like many environmentalists of the time, was quick to tell the story of a place as just the beauty and grandeur of the land. At best, he didn’t include the story of how that land was forcibly taken. At worst, he promoted the racism used to justify that taking. Consider this excerpt from prior Yellowstone historian Lee Whittlesey:

“There seems to have been an effort by early whites in Yellowstone National Park to make the place ‘safe’ for park visitors, not only by physically removing Indians from the park and circulating the rumor that ‘Indians feared the geyser regions,’ but also by attempting to completely segregate the place in culture from its former Indian inhabitants, including their legends and myths.” —Lee Whittlesey

This, to me, highlights the severity of my summer stumbles. During the formation of Yellowstone, and colonial expansion West generally, narratives of the genocide and displacement of Indigenous peoples were either omitted or contorted around the frameworks of white supremacy. The incomplete stories that the young American colonial society told itself permitted their armies to pursue the active displacement of people from the homes they loved: by moving or by killing.

All of these realities are components of Yellowstone’s story, and thus components of the story of the National Parks. My hope this summer was to tell the story of the National Parks using data about visitation. I quickly came to realize that it wasn’t so much about the story I would tell, but what story I would tell.

I believe that a complete story, or even a complete understanding, is impossible. All stories, and all knowledge, can only be partial. As author Dina Gilio-Whitaker highlights, these partial stories can have terrible, persistent ramifications. When telling something’s story, there is an immense responsibility for the storyteller. You choose what knowledge is conveyed, how that thing exists in another’s mind.

This is the responsibility that has me stumbling through these summer weeks. I chuckle at my earlier arrogance of setting out to tell the story of the National Parks. Instead, I happily stumble. If I’m lucky, I will tell a story that is interesting and informative. Maybe a story I learn deeply from while telling it. Maybe a story that reminds us of the immense, complex, often horrific history of the places we go; that helps us make our story of the National Parks just a bit, more, complete.

Reid Lewis, Western Resources Fellows, Land Management Field Practicum Participant, and Symposium Coordinator | Reid is a Master of Forestry candidate at the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. Hailing from Flagstaff, Arizona, he hopes to use his experience in natural resource sampling and GIS to inform the management of drought-resistant, fire healthy forests. Beyond work, Reid loves to sail, hike, and crack open a good book!See what Reid has been up to. | Blog