Preview: Grassland habitats across the world are facing multiple threats due to anthropogenic changes, and species dependent on these ecosystems are suffering as a result. In North America, the Thunder Basin Region represents one of the remaining contiguous expanses of intact grasslands. There are conservation practices already taking place in Thunder Basin, and new approaches are being researched for its continued protection. There are important lessons in considering the role of community based strategies alongside science based decision making for conservation.

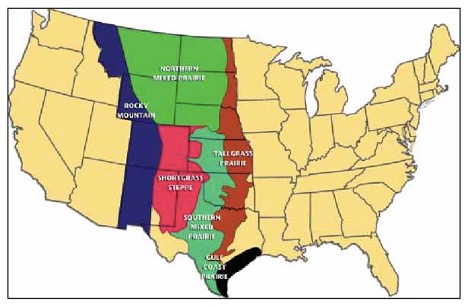

In North America, grasslands were once among the most prominent features of the Western States, from Canadian prairies to the Gulf of Mexico the grassy horizons rolled away into nothingness3. Shortgrass, mixed-grass, and tallgrass prairies are the three main types of grassland ecosystems in North America (Figure 1).

Prairies, steppes, savannahs, veldts – grassland ecosystems are known by many names across the world. However, they all share the status of being among the least protected habitats on the planet1. Grasslands exist because there isn’t enough rain in these regions to support trees, so the landscapes are dotted with a mix of grasses, often giving way to shrublands2. Grasslands plants are often drought-tolerant and adapted to large grazing animals such as zebra, bison, and antelope. These animals eat grasses and support large carnivores, including lions and cheetahs, wolves and people2. Human development that results in grassland conversion to agricultural lands, infrastructure development including roads and highways, mining , and anthropogenic climate change are threatening the continued existence of these systems.

In North America, grasslands were once among the most prominent features of the Western States, from Canadian prairies to the Gulf of Mexico the grassy horizons rolled away into nothingness3. Shortgrass, mixed-grass, and tallgrass prairies are the three main types of grassland ecosystems in North America (Figure 1).

Bison, antelope, and other large mammals roamed these lands freely. The grasses sustained big game populations, and the animals in turn sustained the ecosystems. When prairies are destroyed it also means less habitat availability for resident and migratory animal populations4. We have all heard the tragic tale of colonial settlers in the continent, the conquering of frontiers with the promise of rich fields, the rampant slaughter of bison, the disenfranchisement of native communities, and decades of careless use of resources.

Before settlement as many as 40-60 million bison, and a comparable number of pronghorns were present in the North American grassland3. Almost 2 million acres were habitat for prairie dog species, their habitat reduced by more that 98% by the mid-nineties3.

Grasslands of North America are characterized by unsustainable land use practices as much as, if not more than other habitats across the continent. Urbanization and conversion to agricultural land continues to threaten remaining prairie ecosystems, which makes national grasslands and wildlife refuges critical for their survival4. The Greater Thunder Basin region in Wyoming, comprising nearly 13.2 million acres, represents one of the remaining contiguous expanses of grassland habitat in North America. The ecosystem here is mixed-grass prairie with a diverse mix of grass species. More than fifty grass species can be found here within a 2-acre area, and the nutrient rich soils support a diverse array of species2. The U.S Fish and Wildlife Service has listed eight grassland obligate animal species as “at-risk” of being endangered. The “at-risk” status was in many ways a call for voluntary conservation actions. Without conservation measures the animals could be listed under the Endangered Species Act, prompting the federal government to take actions which could impact private land uses in the area.

The Thunder Basin region represents a patchwork of land uses. Private landowners, and grazing operations are significant stakeholders. Additionally, a mix of federal agencies including the U.S Forest Service (USFS), and Bureau of Land Management (BLM) also manage large portions of the land. Grazing associations in the area are active avenues of collaboration between private ranchers and the USFS. The USFS leases lands to grazing associations with benchmarks for uses that preserve the overall integrity of the landscape, the grazing associations then lease out the land to member ranches. The grazing associations have to follow the grazing management practices as set by federal agencies. They also have the option of setting higher conservation standards for their members than the federal government. Thunder Basin land also has high potential for energy development, subsurface mineral rights are held by the federal government and can be auctioned separately from surface parcels. Coal, oil, and gas development potential of the land cannot be discounted in discussing possible new paths forward for land conservation.

The Thunder Basin Grassland Prairie Ecosystem Association, in partnership with other nonprofits and agencies, has created several conservation agreements to address the needs of this landscape. These voluntary conservation programs cover the breadth of mixed land ownership seen in the region. Private property owners, including ranchers and agricultural producers in the region can enroll their land in the Candidate Conservation Agreement with Assurances (CCAA)5. Some private property owners hold additional grazing leases, contracts, or permits of use on federal lands; these acres can be enrolled in the Candidate Conservation Agreement (CCA)5. Furthermore, lands designated for future energy development including sites for coal mines or oil and gas ventures can be enrolled in the Conservation Agreement (CA)5. The overarching approach of conservation modeled by TBGPEA is necessary for strategic conservation planning that allows the land to be used for various purposes. The Nature Conservancy -Wyoming helped with this effort in an advisory role and continues to coordinate with these stakeholders. The coverage area for TBGPEA activities encompasses five northeastern Wyoming counties and a 10-mile wide area to the west and south of Campbell, Converse, Crook, Niobrara, and Weston Counties. Nineteen agricultural producers and 14 energy companies with land holdings in the coverage area are current members of the association5.

Members to these agreements implement conservation measures on their lands, which protect one of the threatened species. In return, participants receive guarantees that more stringent regulation would not be imposed on their lands, if one of the covered species ever gets listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act. These agreements also allow members to implement conservation measures on properties other than the ones directly enrolled for maximizing benefit. This provision is particularly important for energy development sites, as it allows companies to offset their land use by conserving another piece of land within the coverage areas. Addressing the issue of split surface and mineral rights ownership, while paying attention to energy development potential of the land, is important for the success of any conservation strategies in the region.

This past academic year, I worked with fellow graduate student Katie Pofahl to research another conservation and land management approach in the Thunder Basin region. This approach is called “grassbanking” and it builds on the collaborative nature of grazing leases and member ranching associations, while integrating market-based mechanisms and business models into the framework. We conducted this research for the Nature Conservancy-Wyoming, and our full report can be found here.

Perhaps a bigger lesson lies in the rolling grasslands of Thunder Basin; it provides prospects of learning from past inadequacies and moving forwards with a whole community approach. After nearly 6 years of studying and working with environmental scientists, living in a sphere surrounded by conservationists, thoughtful peers and mentors, and an unconditional devotion among my community to be better stewards of the planet, I’ve come to realize some core principles that guide most of us; justice, integrity, and respect for science.

Environmental managers need to work on multiple fronts that target these social, political, and economic considerations alongside science-based solutions. Conservation cannot succeed without the full collaboration of surrounding and impacted communities. Building an airtight fortress of draconian regulations around our natural resources and keeping everyone out is not a long-term solution. When these fortresses begin to fail, as they often do, access is allowed to certain privileged groups, keeping others from partaking in what should be equal rights for all. A better, more resilient path to protection is to work with communities, safeguarding their long-term interests too. Among other actions we need significantly stronger protections for native lands, re-training programs for displaced energy workers, environmental science education in grade schools, and open conversations with those who don’t agree with this point of view.

There is no environmental protection without environmental justice, and there is no path to landscape conservation without involvement of those who would pay the short-term cost of such conservation. Transformational change, and lasting acts of kindness towards the planet require the hard work of education, empathy, and difficult conversations. It requires us to engage with the human element of impacts. It demands humility, patience, and a deep acknowledgement of our own privileges.

References

- Grasslands. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.worldwildlife.org/habitats/grasslands

- Thunder Basin. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.nature.org/en-us/get-involved/how-to-help/places-we-protect/thunder-basin/

- Chapter 6 GRASSLANDS OF CENTRAL NORTH AMERICA. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/3/y8344e0d.htm

- Service, U. S. F. and W. (n.d.). Saving our native prairies: A landscape conservation approach: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Midwest Region. Retrieved from https://www.fws.gov/midwest/news/nativeprairies.html

- Conservation Highlights. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.tbgpea.org/conservation/highlights

Editing completed by Katie Pofahl

Student Researcher

Humna Sharif, Research Assistant |Humna Sharif is a Master of Environmental Management Candidate at Yale F&ES and is focusing on water resource science and management, and environmental policy analysis during her time at Yale. She graduated from University of Virginia in 2018 with a degree in Environmental Sciences and worked at the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) in Washington D.C. Her portfolio included NFWF’s programs in the Western U.S. including the Northern Great Plains, Northern Rockies, and Sagebrush Landscapes among others. She is interested in exploring the interconnectedness of freshwater systems with land, and how we can address issues of water quantity/quality through ecosystems management practices, and policy changes. See what Humna has been up to. | Blog