Clean and safe water is one of the most precious resources anywhere in the world, but this is especially true for arid regions with growing populations. Southwestern US, known for being hot and dry, is getting even hotter and drier due to climate change.

The Colorado River is the single most important source of water here with upwards of 25 million people depending on it for their water supply. Climate Change is the biggest threat to fresh water in the Southwest, and a mega-drought has slowly dwindled the region’s water supplies in the last two decades. But there are other factors exacerbating an already deteriorating balance between the dwindling water resources, and rising demand.

Renewed interest in uranium mining in the area surrounding the Grand Canyon in Arizona is one such threat. We can remedy this threat with stronger policy frameworks but rollbacks in legacy environmental protection laws over the last few years have emboldened mining interests to continue exploiting the region’s natural resources. Before exploring the links between water contamination and uranium mining, a look at recent regulatory measures related to mining operations around the Grand Canyon is necessary.

Background on Uranium Mining

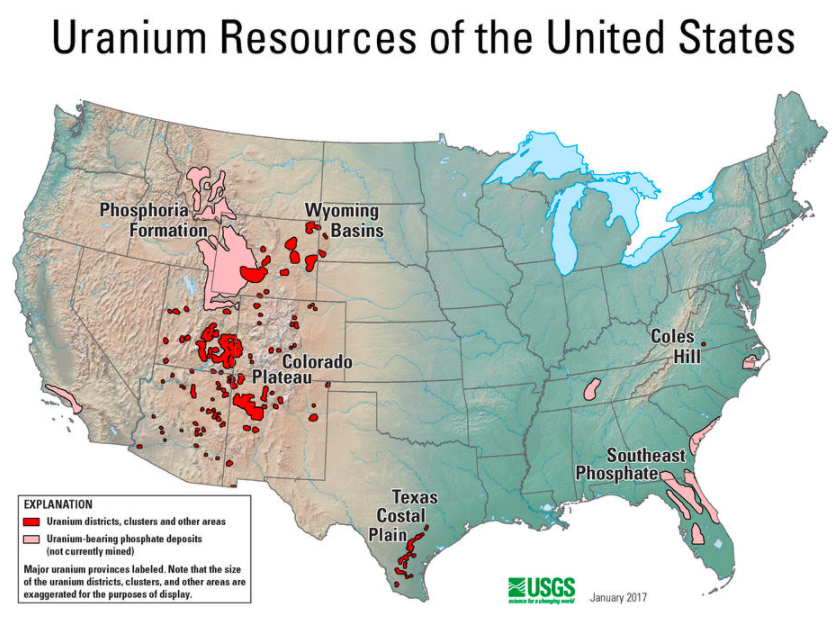

US geological survey data show that most of the country’s uranium deposits are located in the Western states with nearly 1 million acres of land around the Grand Canyon National Park containing these deposits.

(source: US Geological Survey)

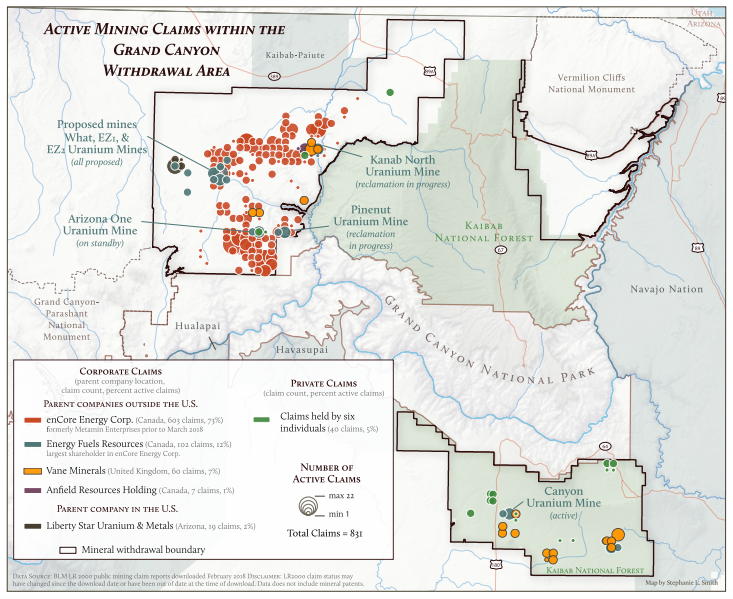

In 2012, President Obama and then Secretary of Interior Ken Salazar announced a moratorium on new mining claims in the area surrounding the Grand Canyon. Concerns over the Colorado River’s water quality, safety of nearby Native American communities, and continued protection of a high tourism area were some of the reasons that led to this decision. However, this ban did not include the existing 3,200 mining claims in the region, and development of 11 uranium mines was expected to continue. The move to ban speculative mining was opposed by pro-mining interests and many republican politicians.

In 2015, work started to reopen the Energy Fuels owned Canyon Mine located six miles from the Grand Canyon National Park, as existing mining projects could continue operations even after the ban. The mine site is in close proximity to drinking water sources for the Havasupai people, and near tourist areas of the Grand Canyon. The Havasupai people brought a lawsuit against the mine for its negative health and environmental impacts, including drinking water contamination.

In 2017, The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals allowed the mine to move forward, but also upheld the Obama era ban on new claims. At this time the House Subcommittee on Energy and Mineral Resources also began reconsidering the mining ban amid concerns of energy security for the country.

In 2019, the Nuclear Fuel Working Group was established at the Department of Energy (DOE) to further explore uranium mining prospects.

In February 2020, the Trump administration asked Congress for $1.5 billion over the next decade to create new nuclear stockpiles. The Trump administration has insisted that domestic uranium deposits are vital for US energy security, but the DOE representatives have admitted that “no immediate national security need has been identified” for the uranium reserve”.

In April 2020, the Nuclear Fuel Working Group released a report titled “Restoring America’s Competitive Nuclear Energy Advantage”. The report laid out policy recommendations and a strategic plan in line with the executive directives to grow and restore the US nuclear reserves.

The first step in the strategic plan is for the US Government to, “take immediate and bold action to revive and strengthen the uranium mining industry, support uranium conversion services, and sustain the current fleet, removing strategic vulnerabilities across the nuclear fuel cycle and restoring a world class workforce to provide benefits to the U.S. and enable the United States to compete in the international market.”

(source: Grand Canyon Trust )

Nexus with Environmental Laws

Mines on federal lands must undergo extensive permitting processes involving multiple federal and state agencies depending on the land ownership patterns of the specific area. New mining projects would commonly require reviews under NEPA, NHPA, and ESA, but over the last few years the Trump administration has significantly rolled back these permitting requirements and weakened legacy environmental protection laws. The Clean Water Act (CWA) regulations that protect “navigable waterways” have also been gutted in the last year. The June 4, 2020 Executive Order, is the latest in the list of regulatory rollbacks that benefits special interests at the detriment of our natural resources.

Robust permitting laws and strong regulatory oversight is necessary for any type of mining because of the massive land footprint and toxic materials that are released in the process, but uranium mining especially poses more risks. Mining for nuclear fuels can expose open spaces to radioactive materials in the form of dust and particulates, as well as cause contamination of water supplies. The weakening of federal permitting regulations makes the establishment of uranium mines close to national park units a clear and present danger to human health and public safety.

The Colorado River winding through the Grand Canyon National Park, as seen from Plateau Point

(source: National Park Service)

Groundwater Contamination

In 2019, Sierra Club’s Grand Canyon Chapter and other environmental groups submitted comments to the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality asking for further review and public hearings/comment period before the granting of an Aquifer Protection Permit.

According to the comments, 10 million gallons of groundwater flooded the mine in 2018, and 9 million gallons the year before. Uranium toxicity levels in the water are consistently higher than safe amounts and these conditions threaten perched and deep aquifers around the mine.

The comments also pointed out the deficiencies of the initial Forest Service Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) that was released in 1986. The EIS stated, “The possibility of significant groundwater contamination is remote. Groundwater flows, if they exist, are likely to be at least 1,000 feet below the lower extremities of the mine,” and that “the low potential for encountering groundwater in the mine effectively eliminates the possibility of contaminating the Redwall-Muav aquifer.”. However, mining operations did intrude on the underlying aquifer rendering regional wells and springs in the Grand Canyon dangerous.

Neither the federal government nor the state of Arizona require monitoring to determine if the water flooding the mine shafts is also reaching the underlying Redwall-Muav aquifer. This is one of the largest aquifers in the state and regulatory agencies haven’t set standards for detecting pollution. Once contaminated with radioactive substances, it would be impossible to clean up the aquifer

Surface Water Contamination and WOTUS Rollback

In 2015, the Obama administration introduced the “Waters of the United States (WOTUS)” rule in an attempt to clarify the legal grey area around what constituted “navigable waterways” under the Clean Water Act (CWA). Through the 2015 version of WOTUS, ephemeral and intermittent streams as well as non-adjacent wetlands could be regulated by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). In 2019, the Trump administration repealed the Obama era WOTUS rule asserting that it was an over-reach of EPA’s authority. The current, much narrow interpretation of WOTUS leaves nearly 60% of the streams in the country that are dry for parts of the year unregulated.

In EPA’s own words, “Ephemeral and intermittent streams are the defining characteristic of many watersheds in dry, arid and semi-arid regions, and serve a critical role in the protection and maintenance of water resources, human health, and the environment”. Yet the failure to regulate these important hydrological features on the federal level leaves water bodies open for exploitation.

The rollback of WOTUS is also making it easier for mines to pollute waterways in the Grand Canyon region. In 2012, the Guardian reported, “at least one creek in the national park is known to be contaminated by uranium, and the government’s environmental impact review found high levels of arsenic from old uranium operations as well as contamination of the Colorado River. A 2019 report by the Grand Canyon Trust states that “several U.S. and tribal government agencies identified 29 water sources on the Navajo Nation with uranium and other radionuclide levels in excess of drinking water standards”.

Horn Creek in the Grand Canyon National Park is currently contaminated with much higher concentrations of uranium than EPA safe limits; it is marked on park maps as “Do Not Drink”. This creek was contaminated by the Orphan Mine, which is now closed but radioactive matter has continued to seep into the water. Under the new WOTUS rule such contamination of park and park adjacent creeks has become much easier.

Mining operations near the canyon have infiltrated groundwater supplies in the past and will continue doing so despite the mining companies’ claims that their operations are safer than ever before. For example, contamination of groundwater in the Redwall-Muav Aquifer would directly impact canyon seeps and springs, many of which are ephemeral in nature. The unique topography of the canyon supports 10 of the 12 classified types of spring waters and according to the National Park Service, most of these are ephemeral or intermittent in nature.

Elves Chasm in the Grand Canyon National Park. Seeps and Springs like these protect species diversity-upto 500 times more than the surrounding environment

(source: Grand Canyon Trust)

The contamination of local creeks and springs that would not be covered under the much narrower interpretation of the WOTUS rule also threatens the water supply of nearby Havasupai and Navajo communities. These creeks and springs eventually feed into the Colorado River, the main water source for nearly 25 million people in the Southwestern US and downstream from the canyon.

Weakened WOTUS regulation makes it easier for mining companies to obtain their CWA permits. Typically mining operations require the CWA Section 404, and 402 permits. The former allows for “discharge of dredged or fill material into navigable waters at specified disposal sites”, and the latter is a National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit which “authorize discharges from discrete conveyances – called point sources – into waters subject to federal jurisdiction”. Since ephemeral or intermittent streams are no longer considered to be federal jurisdiction under the new WOTUS rule, any pollutant discharge to these waters would only be overseen by state or local authorities – a significant reduction in oversight for highly polluting activities.

What happens now?

When the 20 year mining ban was placed in 2012, it was meant to give scientists and federal agencies more time to understand the underlying geographic and hydrologic features of the Grand Canyon. This regulatory action should have been followed up by secure funding mechanisms for new research, but so far federal funding for new studies has been hard to come by. Lack of comprehensive environmental studies is not synonymous with lack of evidence of environmental harm, but mining interests are using this lack of funding to their advantage.

If the ban on new mining claims is lifted, and with already weakened permitting requirements under CWA, NEPA, NHPA, and ESA, uranium mining in the Grand Canyon will permanently destroy priceless natural vistas, and pollute the Colorado River water – all under the pretense of energy security for the country.

It is also important to consider the WOTUS rollback in the context of other weakened environmental laws, one or two uranium mines leaching radioactive materials may not push the Colorado river water beyond safe limits. But when mining is made easier for hundreds of current prospectors, and required permits are issued with much lower safety standards, this sets a dangerous precedent for future contamination – one that would be difficult to walk back.

Humna Sharif, Research Assistant and Western Resources Fellow Humna Sharif is a Master of Environmental Management Candidate at Yale F&ES and is focusing on Water Resource Science & Management, and Environmental Policy Analysis during her time at Yale. She is interested in exploring the interconnectedness of freshwater systems with land, and how we can address issues of water quantity/quality through ecosystems management practices, and policy changes. As a Western Resources Fellow, Humna is working with the National Park Conservation Association (NPCA), and Sustainable Waters on issues of water and land conservation in the Western US. She holds a BA in Environmental Sciences, and Environmental Thought & Practice from the University of Virginia and worked at the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) in Washington D.C prior to beginning her graduate work. See what Humna has been up to. | Blog