I’m writing from Red Canyon Ranch, a working ranch and nature preserve owned by the Nature Conservancy. I’m fortunate to have the opportunity to live at the Ranch this summer while working with Conservancy staff on questions related to beaver restoration and water management.

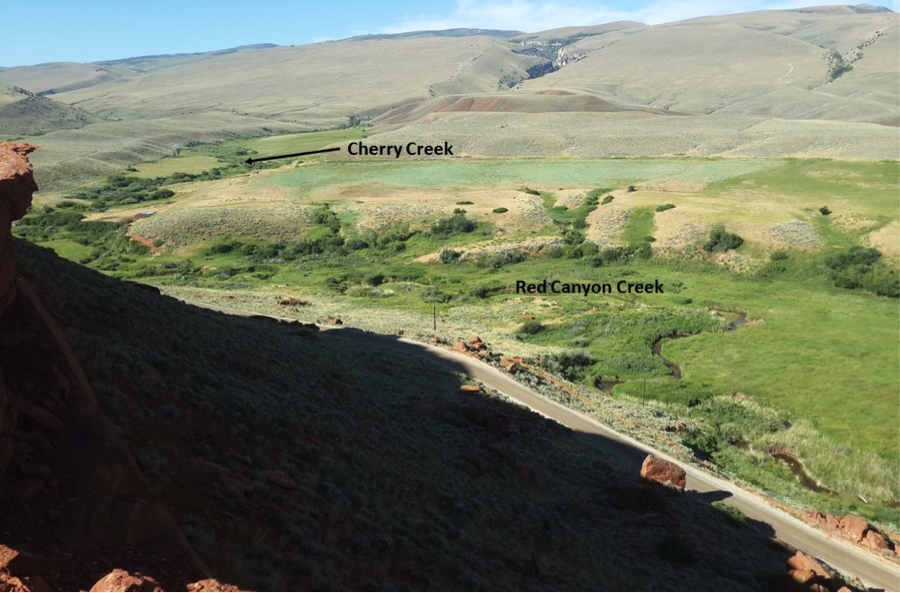

Red Canyon Ranch covers some 5,000 acres in the foothills of the Wind River Mountains in Wyoming. Public lands surround the property on three sides. Bighorn sheep, elk, and antelope graze the Ranch’s broad western slopes, while mule deer, moose and an impressive variety of bird species reside in the valley bottoms. A grizzly that local climbers call ‘Waffles’ roams the rugged upper canyons, wolves haunt the high valley ridges, and the Ranch is home to what the Fish and Game Department calls a ‘locally abundant’ population of prairie rattlesnakes. Though you might not suspect it on such a small stream system, a robust population of brown trout inhabit Red Canyon Creek and its three tributaries, and many more run up from the Little Popo Agie in the autumn to spawn.

The Conservancy bought the property in 1993 to prevent habitat fragmentation and protect the area’s unique biodiversity. Instead of managing the property strictly as a nature preserve, the Conservancy chose to keep the land in production and now leases it out to a local ranching family who share the responsibility and work of stewardship. Alongside the ranching operation, the property also plays host to research groups, long-term studies, and demonstration projects.

Red Canyon is famous for its stunning red cliffs, but the property’s riparian areas are what stand out to me. The term ‘riparian’ refers to the zone where land and water meet. At Red Canyon, these are the streamsides, valley bottoms and wet seeps that dot the hillsides. These lush environments are critical to life in dry places.

Diversions in the foothills channel water from the streams into earthen ditches that move it downwards along the valley contours. Over the years these ditches have picked up stones, sand and gravel from the rivers, sometimes giving them the appearance of natural streams.

Farther down, the ranchers lay orange vinyl across the ditch to cause the water to spill over to flood and irrigate the fields. This flood irrigation creates lush meadows far above the normal reach of streamwaters. The flow from the ditches is eventually squeezed into long, snaking sections of white PVC pipe, pushing the water a little further by cutting seepage losses and concentrating flow.

The confluence of Red Canyon Creek (loaded with red sediment following a massive thunderstorm and multiple landslides) and the Little Popo Agie during peak runoff

Red Canyon Creek has three tributaries: Cherry Creek, Barrett Creek and Deep Creek. Each of the streams is remarkably different, supporting different streamside vegetation, flow patterns, sediment loads, and fish populations. Spring runoff accentuates these differences. Deep Creek for example, runs high and clear while it receives snowmelt directly from high mountain peaks, while Red Canyon Creek becomes brick-red with mud as it cuts through the soft, erodible soils that make the bottomlands so attractive for growing hay. With a smaller watershed than the other tributaries, Barrett Creek starts to run low relatively early in the season. Having four streams with diverse qualities helps create a resilient riparian system at Red Canyon. If one stream is impacted by low snowpack, hot weather, collapsing stream banks, heavy upstream irrigation diversions, or concentrated grazing, for example, fish and other wildlife have other options nearby.

These differences are, in a roundabout way, what brought me to Red Canyon in the first place. John Coffman, the Conservancy’s Land Steward in Southern Wyoming, noticed that Cherry Creek fared much better than Barrett Creek following massive spring flooding in 2014. Why the difference between the two streams? One theory is that Cherry Creek had a family of beavers whose dams acted like speed bumps for the floodwaters, while Barrett lacked beavers and dams to slow the flow. In the fall of 2016 I started working with John on a white paper designed to communicate the benefits of beaver to ranchers and public land managers.

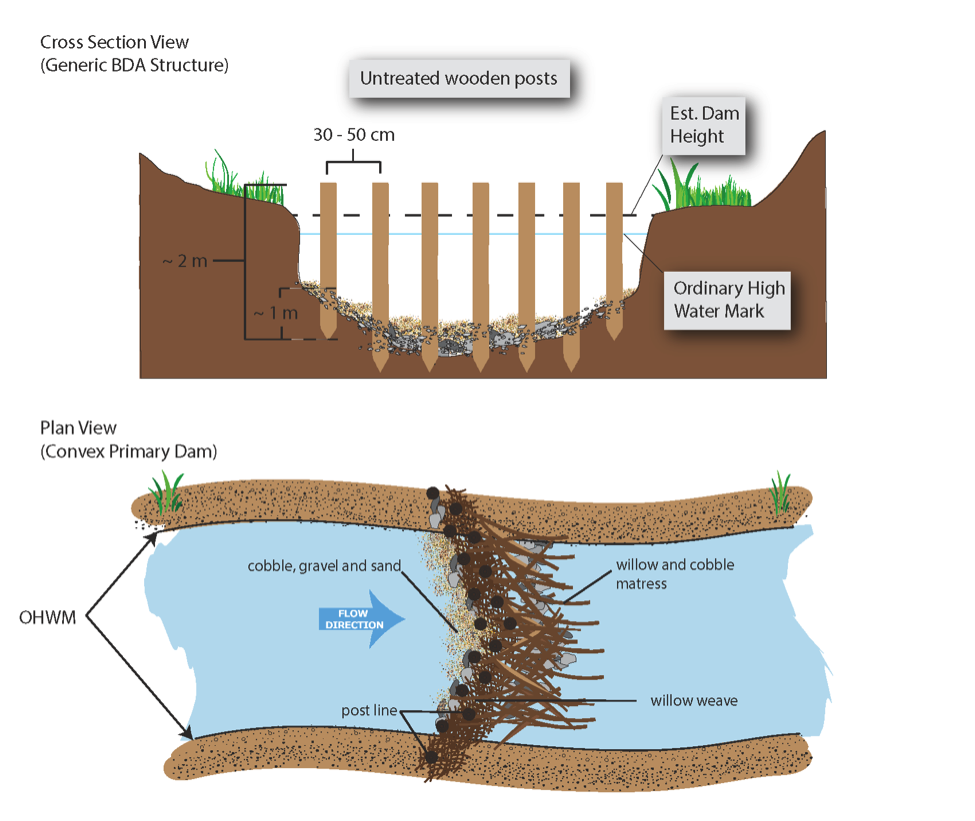

This summer I’m taking this work to the field, monitoring beaver activity on the property and collecting pre-project information on the riparian environment in advance of installing Beaver Dam Analogs (BDAs). Beaver Dam Analogs are human-built structures that mimic the effects of natural beavers dams. Essentially, they’re posts pounded in the streambed, with willows weaved through. By raising the water table to grow streamside willow thickets, creating deep pools for beaver to hide in, and forming firm ‘starter’ dams for beavers to build on, BDAs are designed to to give beaver a foothold to move back in and work on degraded stream sections. At Red Canyon, there are stretches of stream that have deeply incised banks and which lack willow thickets to hold the banks, shade the stream and provide cover for wildlife. Entire meadows have been left high and dry (unless there’s irrigation water above) by sinking water tables. The BDA project at Red Canyon is one of the first projects of its kind in Wyoming, and it will be a learning opportunity that will hopefully inspire and inform similar efforts elsewhere in the state.

Cross section schematic of a Beaver Dam Analog (BDA). Figure from the Beaver Restoration Guidebook (2015)

This demonstration project is one of many being pursued on TNC properties. These projects reflect a broader management philosophy recently articulated by TNC president Mark Tercek in the January 2017 issue of Nature Conservancy:

“We see our fieldwork as more than simply problem solving at a single place. We envision projects as research and development labs that will lead to conservation models that TNC, our partners and others can rapidly apply elsewhere. We view this approach as our best hope for scaling up our work to meet the conservation challenges of the 21st century”

Switching gears and looking beyond Red Canyon, another part of my work with the Conservancy this summer involves water management across the state. In its most recent strategic plan, TNC Wyoming prioritized developing collaborative water projects that align the interests of agricultural and municipal water users with ecological needs. To this end, I’m working with Conservancy staff and local partners to identify project opportunities that demonstrate the feasibility of supporting in-stream flow within the context of existing regulation and water rights.

While I do spend a good deal of my time on the project reading plans and reports, tracking down datasets, and mapping, I’ve also had opportunities to tour irrigation systems, attend water workshops, and spend countless hours along streams, all of which contributes to my understanding of the social and physical infrastructure that moves water in the state.

Stay tuned for an end-of-summer update that will be coming all too soon.