When’s the last time you were dancing? Really going for it, with sweat and chaos and flashing lights? For me it was New Year’s Eve in a quaint, bizarre ballroom that seemed better designed for blackbox theater than a late night of revelry. It was warm and there was poor air circulation; a strange entry point for a year of a respiratory pandemic. On the wall, a local TV network repeatedly flashed their year-welcoming mantra:

2020: Perfect Vision.

The irony is almost painful, how a lack of foresight (and action) has caused so much preventable death and despair. Over the summer, as I’ve occasionally reflected back to the start of the year and the significance of a coincidental number and a local television’s message, I’ve thought more and more about vision and perspective. I’ve thought about what we see and what we don’t see based on the narratives we’ve been told, and how this vision – or lack thereof – shapes the impact we have on the world.

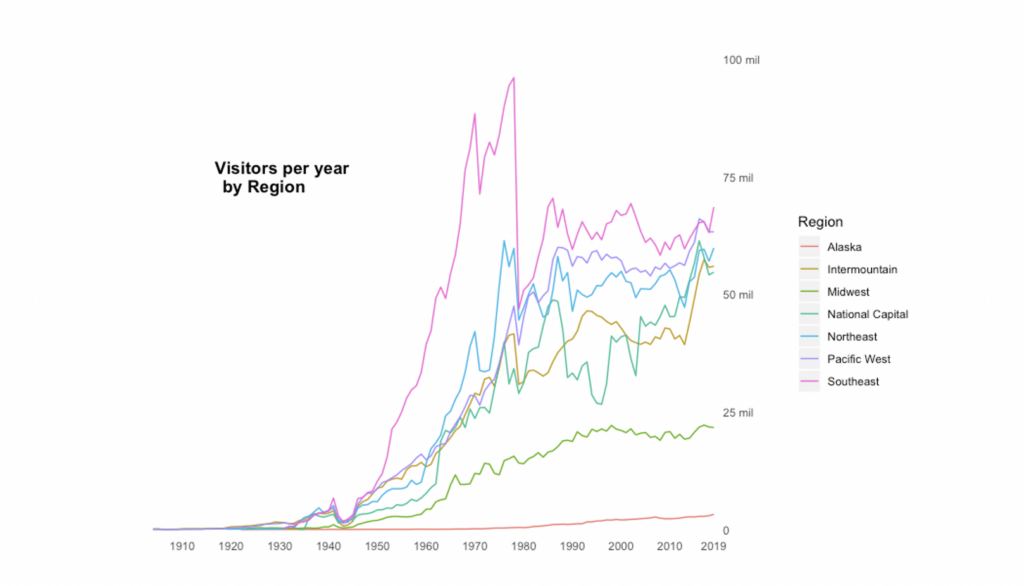

All of this thought took place in the context of immense fortune; I had my health, a stable home, and knew where my next meal was coming from. From this luxury of safety, I was able to work on a project during an incredibly tumultuous summer. With access to a great dataset and decent internet, I set out to remotely explore how people used the National Parks over the years.

As I worked on this project I continued to think more and more about narratives (discussed more fully here). What informed my own narrative about the National Parks? What narrative could I tell with the dataset I had? Who would it benefit?

Before thinking about the goal of my summer’s work, I hadn’t rigorously challenged my own narratives of the National Parks. Eventually, after gaining perspective from some great resources, I realized that starting the history of National Parks in 1901 (the first visitation data point) was not only a large omission, but a massive injustice to the Indigenous people who have powerful connections to the land. How do you convey narratives of Indigenous genocide, erasure, survivance, and immense cultural diversity from a dataset limited to one variable through a small slice of time?

As I learned more about Indigenous relationships with the lands we call the National Parks, I started to realize how difficult it would be to say something of significance. Instead, I committed the rest of my summer to learning. Throughout my past two years as a student of forestry, I’ve learned much about the forests around me, but little about the Indigenous nations that connect with them. Some fellow friends and colleagues (the Yale Forest Fellows) felt similarly, and we formed the Yale Forests Reading Group to unpack the past, present, and future of the forests we studied by centering the experiences of Indigenous communities.

Our suspicion was that we weren’t the only people eager to learn more about Indigenous perspectives and histories of the forests of the Northeast and beyond, so we structured the group to be public facing through Instagram posts and an email listserv. We hoped to reach a few dozen folks who wanted to learn with us, engaging with comments and feedback from time to time. As I write this reflection, with summer turning to fall, we have 140 listserv members and more than 1,000 people engaging through Instagram. The content we’ve been learning from, that so many Indigenous scholars and activists have shared, has been revelatory in how I view and understand the Northeast: narratives of theft, greed, strength, survivance, sorrow, and joy. Learning by centering narratives of Indigenous nations of the Northeast will forever enrich the future I hope to help create.

Reid Lewis, Western Resources Fellows, Land Management Field Practicum Participant, and Symposium Coordinator | Reid is a Master of Forestry candidate at the Yale School of the Environment. Hailing from Flagstaff, Arizona, he hopes to use his experience in natural resource sampling and GIS to inform the management of drought-resistant, fire healthy forests. Beyond work, Reid loves to sail, hike, and crack open a good book! See what Reid has been up to. | Blog